When one goes to

Clark today, he passes avenues like C.M. Recto, G. Puyat, M.A. Roxas, K.

Laxamana---all names of Filipino statesmen, heroes and personalities. But in

the not-so-distant past, when Clark was still a piece of America in Pampanga,

its major thoroughfares and buildings

bore ‘stateside’ names like Dyess, O’Leary, Kelly, Levin, Mitchell, Wagner

among others. Not many Kapampangans know the faces behind these names today, so

here are a few of them.

**********

CAMP STOTSENBURG,

named after Col. John Miller Stotsenburg

The future Clark Air Base started as an unnamed camp

established six miles northwest of Angeles town by soldiers of the 5th

U.S. Cavalry regiment on Dec. 26, 1902.

It was the tradition to name camps after American soldiers killed in the

Philippine-American War, and that was how Col. John M. Stotsenburg, killed

in action on April 23, 1899 near Quinga, Bulacan, came to be immortalized when

the cavalry post was named after him. A graduate of West Point (1881) and the Infantry and cavalry School at Fort

Leavenworth, Kansas (1897), Col. Stotsenburg was assigned to the Philippines to

lead the 1st Nebraska Regiment as their battalion commander. In an

unplanned engagement on April 23, Col. Stotsenburg ordered an immediate advance

to fight the Filipinos. Moments later, he was shot in the chest and killed; he

was only 40 years old.

CLARK FIELD, named

after Maj. Harold Melville Clark

The first airplane landing field were just long dirt

landings scraped from the ground in 1919. Eventually, a more expansive airfield

was built, asphalted and expanded before World War II. The airfield would be

named after Maj. Harold M. Clark, a Philippine-educated American (Manila High

School, 1910, future president Manuel A. Roxas was a classmate), who received

his pilot’s wings in March 1917. One of the first aviators in Hawaii, Clark was

flying his seaplane in the Panama Canal Zone when it crashed on May 2, 1919.

The young pilot was killed but his name would live on, overshadowing the

original camp name, and by the 1960s, the camp complex together with its airfields, would be known

Clark Field or Clark Air Base.

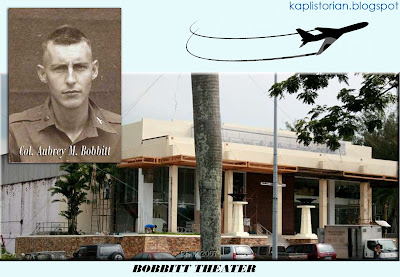

BOBBITT THEATER,

named after Col. Aubrey Malcolm Bobbitt

The popular movie house of Clark that was favorite

of American servicemen, their families,

as well as Wagner High teens, screened the latest blockbuster films from the

60s thru the 90s--from “The Thing” “Saturday Night Fever” ,”Jaws”, to “American

Werewolf in London”. Bobbitt stood next to the BX, across from what used to be

the main gas station, in the same parking lot of what was once the American

Express Bank. It was named after Col. Aubrey M. Bobbitt (b. Jan. 25, 1940/d.

Aug. 29, 1971), base commander and the commander of the 6200th Air

Base Wing, in September 1972. Col. Bobbitt had an illustrious 29-year career in

the U.S. military, serving in Newfoundland, Europe and the Philippines. He died

at the USAF Hospital of heart attack. Bobbitt Theater, post-Pinatubo, it became

a hotel, a cocktail lounge (“Forbidden City”), and is now part of the Widus Hotel and Casino

complex.

BONG HIGHWAY, named after Maj. Richard Bong (now Manuel L. Quezon Avenue)

Bong Highway has such a local ring to it, sounding much like

a common Pinoy nickname. But this major Clark road which leads to the Mimosa

main gate (now a Filinvest property),was

named after a World War II Medal of Honor recipient, Major Richard Ira

"Dick" Bong (b.Sep. 24, 1920/d. Aug. 6, 1945). One of t host decorated

fighter pilots, Major Bong is known for downing 40 Japanese aircrafts in his

lifetime. Tragically, he died in California while testing a jet aircraft before

the war ended.

DYESS AVENUE,

named after Ofcr. William Edwin Dyess (now, C.M. Recto Highway)

William Edwin "Ed" Dyess (August 9, 1916 –

December 22, 1943) was an officer of the United States Army Air Corps during

World War II. He was in command of the 21st Pursuit Squadron tasked

to defend Clark. He was captured after the Allied loss at the Battle of Bataan

and endured the subsequent Bataan Death March. After a year in captivity, he

escaped and spent three months on the run before being evacuated from the

Philippines by a U.S. submarine. Once back in the U.S., he recounted the story

of his capture and imprisonment, providing the first widely published

eye-witness account of the brutality of the Death March. He returned to duty in

the Army Air Forces but was killed in a training accident months later.

One of the historic buildings in Clark Air Base was the Kelly Theater, constructed in 1953, the only cinema house in Clark and the venue of many stage plays and cultural shows. There was an earlier Kelly Theater built earlier—in 1947—that was converted from an old gymnasium. Both theatres were names after B-17 pilot Capt. Colin P. Kelly Jr. (b.Jul. 11, 1915/d. Dec. 10, 1941) who died in action against the Japanese forces in 1941. Kelly’s damaged plane, while returning from a bombing run, blew up near Clark Field after being engaged by enemy forces. Capt. Kelly was declared America’s first hero of WWII by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The memorial statue of the fallen captain was inaugurated on the theater grounds on 10 Dec. 2007—the 66th year of his passing. Kelly Theater, located at the cor. Ninoy Aquino Ave. and Foxhound St., survived Mt. Pinatubo, but eventually everything from the seats to the roof and front walls were stolen.

MEYER LEVIN

GYMNASIUM, named after Master Sgt. Meyer Levin

The gymnasium facility on Dau Avenue, east of the Parade

Ground was named after Meyer Levin in 1955, a master sergeant of the U.S. Army

Air Corps. Raised in Brooklyn, New York, Levin (b.Jun 5, 1916/d.Jan. 7, 1943)—who

had wanted to become an aviator—became a bombardier and flew with Capt. Colin

Kelly after the Japanese attack of Clark Field. During his last mission on

January 7, 1943, Levin volunteered to bomb the Japanese convoy ships that was

approaching Australia. The weather worsened, and as the plane used up its fuel,

the crew bailed out as the planed ditched the water. Levin remained in the

plane to release the rafts that saved his crew. He died in the crash and is

listed as one of those missing at Manila National Cemetery. Levin was awarded

the Distinguished Flying Cross (for

successfully bombing the Japanese warship “Haruna”) and a Purple Heart for his

heroic war feats.

MITCHELL HIGHWAY,

named after Brig. Gen. William Lendrum Mitchell, (now J. Abad Santos Avenue)

One of the most travelled roads in Clark—the Mitchell

Highway-- stretches all the way from the Mars Station, then passes close to the

Parade Grounds, and leads all the way to the Friendship Gate. It was named

Philippine-American war veteran, Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell (b.Dec. 29,

1879/d.Feb. 19, 1936), regarded as the father of the United Sates Air Force. Gen.

Mitchell also saw action during World War I in France, and even commanded the American

air combat units in that country post-war. In 1924, he returned to Pampanga to revisit Camp Stotsenburg where he even gave flying

lessons to Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, whom he had helped capture. The North American

B-25 Mitchell—an American military aircraft design—was also named in his honor.

WAGNER HIGH SCHOOL,

named after 1st Lt. Boyd David Wagner

The beginnings of Wagner High School and Middle School

could be traced back in 1957-58 when the Grades 7-12 of Wurtsmith High transferred

to individual wooden buildings at the former Chapel Center. That site that will

eventually be renamed Wagner High School. The school was named after 1st Lt. Boyd

David Wagner, of the U.S. Army Air Corps, who commanded the 17th

Pursuit Squadron that was ordered to protect Clark. On Dec. 14, 1941 shot down

four Japanese airplanes, and 2 days later, downed another enemy aircraft at

Vigan. Thus, he became the first American World War II Ace, and for which he

earned him a Distinguished Service Cross. Wagner was nearly blinded in the

Lingayen Gulf battle, but survived and evacuated to Australia where he

recovered.Later, he was sent back to the U.S. to train new fighter pilots.

On Nov. 29, 1942, Col. Wagner

disappeared while on a flight from Florida to Alabama. His plane wreckage was

found six weeks later, some 4 miles north of Freeport, Florida. His remains are

buried at Grandview Cemetery, Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

WURTSMITH MEMORIAL SCHOOL, named after Maj. Gen. Paul Bernard Wurstmith

BONUS!

A hill in Clark

bears a peculiar name, because it was not named after a person, or even after a

flower, as its name suggests.

LILY HILL

Lilly Hill first appeared on an 1898 map, and is thought

to have been derived from the Kapampangan

word “lili”, which means “lost”. The Americanized name was apt because it

was easy to get lost on that hill which stood separately from other hills in

the area. Used as an observation point by Americans from 1903--42, it was also

used by the Japanese for the same purpose. It would become the stronghold of

the Kembu Group which defended Clark from late 1944-45. Post-war, a USAF

aircraft warning and control unit was put up in the summit until 1962. A Buddhits

shrine was built on the hilltop by the Japanese in 1998 on the 54th commemoration of the Kamikaze. It features

a large 5-ton granite statue of Kannon, the "Goddess of Peace ".

SOURCES:

Camp Stotsenburg:

Pix of Camp Stotsenburg: Alex Castro Collection

Pix of Col. John Stotsenburg:

Clark Air Base:

Pix,:Harold Clark: An Annotated Pictorial History of Clark Air

Base, by David Rosmer

Bobbitt Theater:

Pix of Bobbitt Theater: www.margaritastation.com

Pix of Aubrey Bobbitt: https://stalagluft3.wordpress.com/2015/07/16/stalag-luft-iii-newsletter-august-2015-reunion-agenda/

Bong Avenue:

Pix: Welcome to Clark Air Base, Guardian of Philippine Defense booklet

Pix of Richard Bong: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Bong

Dyess Highway:

Pix: Welcome to Clark Air Base, Guardian of Philippine Defense booklet

Pix of William Dyess: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_E._Dyess

Kelly Theater:

Pix: An Annotated Pictorial History of Clark Air Base, by David Rosmer

Pix of Colin P. Kelly: Aces of WW2, http://acesofww2.com/bombers/41/

Meyer Levin Gym:

Pix: An Annotated Pictorial History of Clark Air Base, by David Rosmer

Pix of Meyer Levin: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meyer_Levin_(military)

Mitchell Highway:

Pix: Welcome to Clark Air Base, Guardian of Philippine Defense booklet

Pix of Gen. Billy Mitchell: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Mitchell

Wagner High School:

Pix of Boyd Wagner: Photograph by Carl Mydans for TIME & LIFE

Pictures), (Colourised by Doug)

Pix: Wagner High School, 1971, collection of K. Morgan

Wurtsmith Elem. School:

Pix of Wurtsmith School: http://www.clarkab.org/history/

Pix of Gen Paul Wurtsmith: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Wurtsmith

Lily Hill:

Pix: An Annotated Pictorial History of Clark Air Base, by David Rosmer

Images:

Pix; clarksubic.com

Pix; clarksubic.com